An A to Z of the Chiswick House Archives: M is for Mulberry

In the latest in our A-Z series, volunteer archivist Cluny Wells researches the history of our magnificent mulberries.

Mulberries at Chiswick House & Gardens

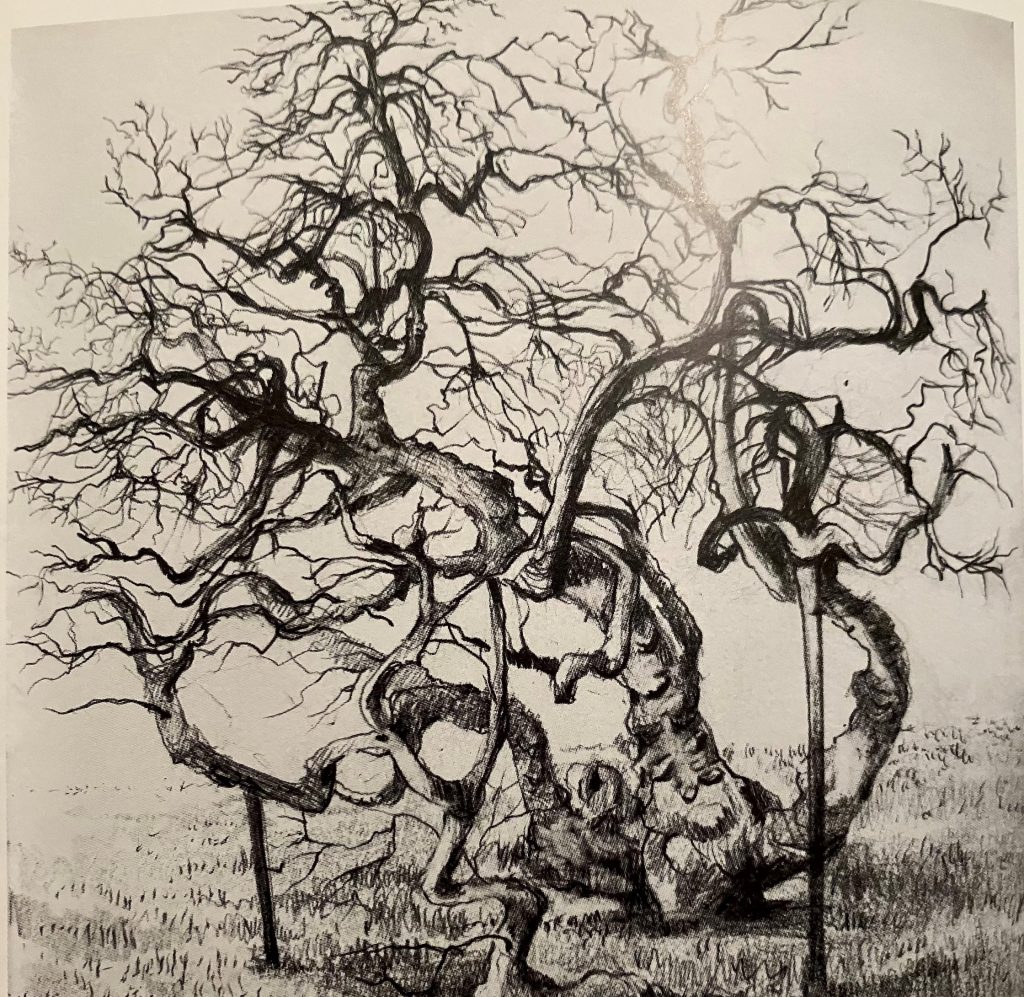

In 2021, Peter Coles, the author of the book Mulberry, came to measure and photograph our Mulberry trees in the Kitchen Garden, as part of his research into ancient mulberry trees growing in and around London.

The mulberry in the Kitchen Garden was easier to measure than the other, whose roots are in the garden of Paxton House, and grows over the wall into the grounds. Peter was invited to view it with the permission of the tenant living there. Peter shared the statistics of the tree growing at the back of the Kitchen Garden with us:

- Circumference: 207cm

- Height: 7.5m

Digging into the archives, the details of the sale of Moreton Hall (1811/1812) mentions the two large black mulberry trees within or near to its Kitchen Garden. It seems that the tree in the Kitchen Garden was planted in the late 17th or early 18th century, and Peter thinks the trees could already have been over 100 years old when the 6th Duke of Devonshire purchased the Moreton Hall estate in 1812 and added it to his lands.

Morus Londinium

These two trees, now considered to be Heritage Mulberries, have now been included in the interactive map of Morus Londinium, an online interactive map of ancient mulberry trees in London, created by Philip Coles. On the map you can see our trees, even though one is growing in a private garden.

There are some very old mulberries in West London. One is in the garden of William Hogarth’s House, and there are others in the garden of Syon House, Isleworth. The trees at Syon may be the remnants of an orchard of a 15th century monastery, dissolved by Henry VIII around 1536.

The mulberry trees found at Chiswick, Hogarth’s House and elsewhere in London are all Morus nigra -the black mulberry. These were introduced by the Romans when they established Londinium around 43 CE, for their taste and shade. Black mulberries were often planted in the grounds of monasteries for the sweet taste of the fruit and the medicinal properties the tree offered. After the dissolution of those monasteries the mulberries were sometimes left standing, even though the people and buildings related to them were long gone.

Royal silks

Lullingstone Silk Farm in Kent, was the only silk farm in Britain, and it forged a strong connection with the Royal family in the 1930s. It was started by Lady Zoe Hart Dyke, who, as a teenager, went to boarding school in Tours in France, and had secretly kept and fed silkworms in her bedroom. The farm went on to produce the silk for King George and Queen Elizabeth’s coronation robes in 1937 and Queen Elizabeth II’s wedding dress in 1947, as well as producing parachutes during the Second World War.

Robert Goodden bought the business in the late 1970s and moved it to his family property, Compton House near Sherborne, Dorset, just in time to make the silk for Princess Diana’s ivory silk taffeta wedding dress, designed by David and Elizabeth Emanuel, in 1981. Goodden’s silkworms provided 11,000 strands of raw silk for Diana’s dress, but it wasn’t enough for the Emanuels’ huge taffeta creation, so the difference was made up with imported silk.

Mulberries and the silk trade

The silk trade, which stretched over most of the world from China, where it started over 4000 years ago, is too large a subject to cover a here, but it has to be referred to as the different varieties of mulberry are linked. The main link is that the silkworm can eat both the white and black variety of mulberry.

The white mulberry, Morus alba was indigenous to China, and vast plantations of up to 25,000 trees were cultivated. The Chinese mastered ways to prune the trees to a manageable size and mechanically harvest their leaves, over 2,000 years ahead of other cultures in their practice of sericulture.

As silk making spread through the Byzantine Empire, Persia, Greece, Spain, Sicily, Italy and France, the Morus nigra (black mulberry), was used. The kind of silk produced by this tree, though a rougher type of silk, was in fact liked by many people, but not such an efficient plant in the manufacturing of silk. These cultures then moved on to Morus alba as used in China and Japan.

The Morus alba has played an enormous role in the economic and cultural prosperity of China for many many years, even with fluctuations in success. Today global trade in cocoons of raw silk is worth over U.S.$1.7billion a year to China.

Evidence has recently been uncovered that the Harappan people of the Indus Valley (modern Pakistan) started farming silk at around the same time as China, using a wild species of moth.

Silkworms and Mulberries

There seems to be a symbiotic relationship between the silk moth Bombyx mori and the mulberry leaves. There are chemical compounds in the tree that attract the silkworm to the leaf. So far, so simple… but now the TWIST… the stem and leaves of all species of mulberry contain a milky latex, fatal to most herbivorous insects… EXCEPT to the larvae of both the wild and domesticated silk moth! This little known (to me) fact has a significance to recent medical research.

Nutrition and Medicine

In different areas of the world and over the centuries all the parts of the mulberry tree have been used to treat various ailments.

Horace wrote in Odes, Satyrs and Epistles –

I’ll give him Health, who when his Meals are done

Eats juicy Mulberries, pluck’d before the Sun

Doth rise too high

Native Americans, observed in the mid 1500s, enjoyed the fruit of their indigenous red mulberry.

Recently the nutritional value of the mulberry has been recognised by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. The health benefits of raw mulberry fruit are many – they contain helpful amounts of potassium, manganese and magnesium and high levels of iron to combat anaemia. It can also be useful in reducing blood sugar levels in order to treat type 2 diabetes. This is apparently linked to the ability of the mulberry sap to kill off most insect predators (except the silk worm larvae) because in that process it interferes with pathways which would normally absorb sugars. See reference below.**

Mulberries in Arts and Culture, Myths and folklore

Artists such as Van Gogh, Xanthe Mosley and Liang Shaoji have made art works depicting or related to the mulberry tree.

As mulberry wood is very rare, the wood is only used very occasionally. Following the storm of 1987 there were more mulberry wood available in the UK for joiners and cabinet makers to use.

Musical instruments are made from mulberry wood in Iran, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan. An example is the stringed instrument called the ‘Tar’.

‘Fu sang’– the leaning mulberry, ‘the silkworm horse’, and ‘the Hollow Mulberry’ are some ancient Chinese myths involving the mulberry. Meanwhile, “Here we go round the mulberry bush” is an English rhyme where young children enact everyday actions like washing hands, in a circle dance with some singing.

Shakespeare wrote about mulberries, for example in Midsummer Nights’ Dream – Titania speech to the fairies tells them to be kind and feed Bottom with “purple grapes, green figs and mulberries”.

The Bard planted a mulberry tree in his garden in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1597, where he lived until his death. Sadly in 1756, 150 years after Shakespeare’s death, a subsequent owner of his house, the Reverend Francis Gastrell, got fed up with strangers milling around his house, breaking twigs off the mulberry tree branches and chopped the tree down. This angered the locals who threw stones at his windows. The Vicar, in a fit of pique, eventually demolished the house and left the town soon after.

We shall end with the words for a song written in honour of Shakespeare and his mulberry tree by David Garrick, the great Shakespearean actor and good friend of Lord Burlington. Garrick refers to the goblet carved for him from Shakespeare’s felled tree.

Behold this fair goblet, ‘‘twas carved from the tree,

Which, O my sweet SHAKESPEARE, was planted by thee;

As a relick I kiss it, and bow at the shrine,

What comes from thy hand must ever be divine!

All shall yield to the Mulberry tree

Bend to thee, Blest Mulberry,

Matchless was he

Who planted thee,

And thou like him immortal be!

Sources:

Mulberry. Peter Coles. 2019

Silk, Slaves and Stupas. Susan Whitfield. 2018

Mulberry, The material culture of mulberry trees. S.J. Bowe. 2015

*”Metabolic Effects of Mulberry Leaves. Potential Benefits in Type 2 Diabetes and Hyperuricemia”, in Evidence based complementary Alternative Medicine. 5 December 2013.