An A to Z of the Chiswick House Archives: O for Obelisks

We have not one but two grand obelisks in our Gardens! In the latest in our A-Z series, volunteer archivist Cluny Wells delves into the history and significance of these structures with roots in Ancient Egypt.

A brief history of obelisks

Obelisks were first constructed over 4000 years ago in Ancient Egypt as monolithic structures, and were often in pairs. In obelisk: A History (Source 1), the authors suggested that “to the Egyptians, the obelisk was the symbol of the pharaoh’s right to rule and connection to the divine.” As well as being erected in commanding positions over the general populace, they were raised and carefully positioned so the first and last light of day would touch their lofty Pyramid peaks, so honouring the sun God, Ra.

Obelisks also functioned in other ways – they performed as solar clocks, sundials, and could be used to determine latitude and seasons. Joshua J Mark, historian, stated that the obelisks were raised in pairs in keeping with the Egyptian values of balance and harmony – “the essential unity of existence through the alignment and harmonisation of opposites.” Wilkinson, R (Source 2).

The earliest known obelisk to have been built, (and remains to this day) in Heliopolis, is the obelisk of Senusret. It dates back to the 12th dynasty, and is over 20 metres tall and cut from red granite.

Chiswick obelisks

The two obelisks at Chiswick House & Gardens were constructed just over 300 years ago, were designed by Richard Boyle – the 3rd Earl of Burlington – the first one around the time that he began working on his gardens, and the second not long after he had built his Villa. Both of these now have Grade 1 listing.

The obelisk in the Orange Tree garden, together with the pool and the Ionic Temple, was in place by 1726/7, before Kent’s involvement in the garden design at Chiswick. It features in several garden scenes painted by Rysbrack for Lord Burlington .

In 1940, a year after the start of WW2, the scene was again painted, this time by Archibald Standish Hartrick. as part of the Recording Britain Collection. This Project was encouraged by Sir Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery, and it had two main aims: to record the scenes and lives of the British at that time, and to help give artists, who might be suffering in wartime, some paid work.

Chiswick’s other obelisk was erected in front of Burlington Gate in 1732 with an antique sculpture on its base (known as a ‘bas relief’) from the Arundel collection. A whimsical sketch by Kent of this obelisk in the moonlight with himself seated and rabbits playing was sent as part of a message from him to Burlington stating how much he was looking forward to seeing him again.

A grant from the Wolfson Foundation in 2006, allowed an advance of the Heritage Lottery Fund bid to allow some restoration of the Burlington Gate and obelisk.

Between 1728 and 1734 both Pieter Andreas Rysbrack and Hyacinthe Rigaud, notable painters, depicted the Villa at Chiswick with obelisk- shaped chimneys, soon after its construction, and yet surveys done by Rocque in 1736, and Lambert in 1742, show the chimneys to be straight. The change was made to counteract the lack of updraft given by the obelisk- shaped chimneys. The Ministry of Works re-instated the obelisk chimneys on the Villa in the restoration of 1956/7, although it seems that baroque architect and inspiration of Chiswick House, Andrea Palladio, would never have used obelisk chimneys, they were a feature used by another Italian architect, Vincenzo Scamozzi, .

Other Notable international obelisks

The most iconic obelisk which was moved from Egypt to Rome, is the Vatican obelisk in St Peter’s Square, measuring 25 metres in height. It was brought to Rome by Emperor Caligula in 37 CE. The tallest standing obelisk in Rome however, is the Lateran obelisk at 32.2 metres, reinstated beside the Lateran Basilica. It is one of two obelisks from the Karnak Temple – the other being the obelisk of Theodosius, taken by Emperor Theodesius from Alexandria to Istanbul, in 390 CE.

In 1819, Sir William Bankes, brought a small obelisk back from Philae to Kingston Lacy Hall, Dorset. The Bankes obelisk, together with the Rosetta Stone, helped with the deciphering of the hieroglyphic language.

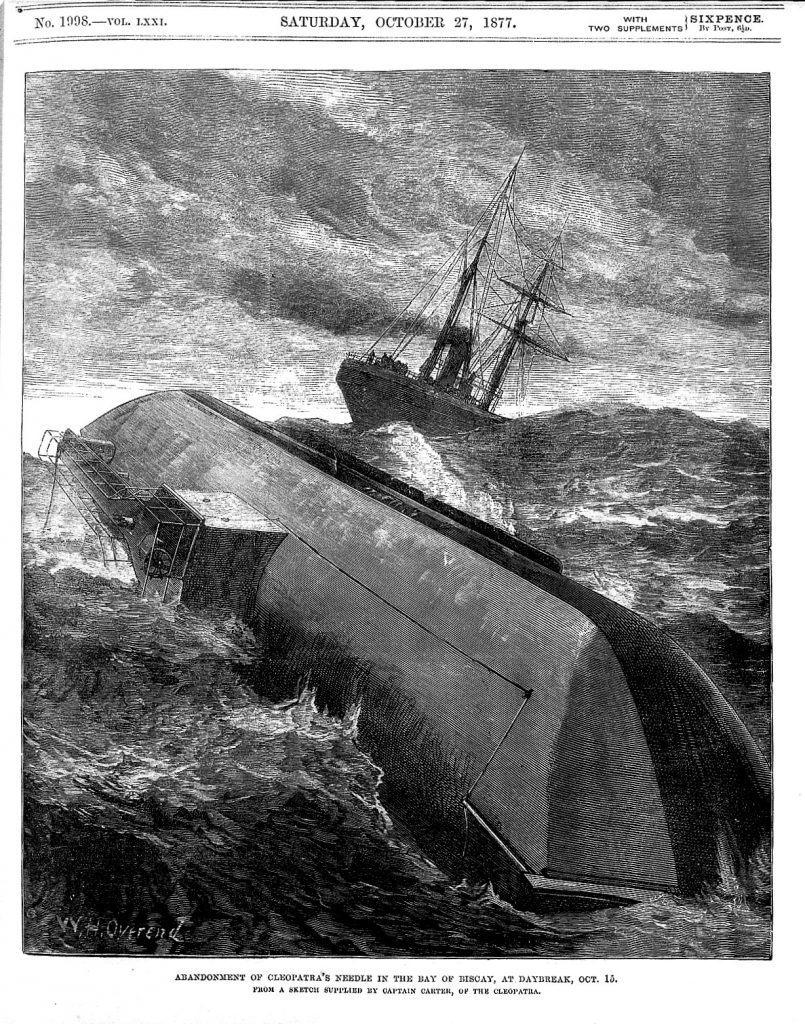

Three more Ancient Egyptian obelisks which were re-erected outside Egypt – two from Heliopolis, later known as Cleopatra’s Needles destined for London and New York, and one other from Luxor which went to the Place de La Concorde, Paris. The Needles was moved from Heliopolis to Alexandria in Roman times and then in the 19th century they went their separate ways one to London and the other to New York. Egypt was by now under Ottoman rule. The London one was presented to the British by Muhammad Ali Pasha in 1819, but it did not arrive until 1878, spending over 60 years waiting in Alexandria for shipping to be arranged. The obelisk weighed over 200 tonnes . A cylindrical iron barge was built to encase the obelisk, known as Cleopatra, and this would be towed by a ship called Olga.

During a bad storm in the Bay of Biscay on 15th October 1877, Cleopatra broke free of the ship and was lost for a while. Unfortunately, six sailors lost their lives during that stormy night. The obelisk Cleopatra was found by another steamship, the Fitzmaurice, which continued towing it to its final destination on the Thames Embankment. The Other Needle, destined for New York, arrived in 1881 without problems.

A Dedication to a Remarkable Woman

William , 2nd Earl of Strafford, and owner of Wentworth Castle Gardens erected an obelisk in his gardens as a dedication to Lady Mary Wortley Montagu for her achievements in bringing a smallpox inoculation from Turkey to Britain in 1720. William’s parents had chosen to have him and his three sibling inoculated, and as a young man he had met Lady Mary. She also had her own children inoculated, illustrating her belief in the process.

Masonic links with obelisks

From the beginning of the 18th century, many Freemasons believed there was an important link between Freemasonry and Ancient Egypt, seen as a mystical place. Until the hieroglyphic language was deciphered in the 1820s, many believed that it was a divine language depicted in stone. Freemasons believe that obelisks are symbols of the sun, resurrection and light. Lord Burlington’s use of Egyptian features in his grounds such as the obelisks he designed can be viewed as showing connections with the Roman Emperor Augustus.

Burlington’s purpose of designing his Gardens and Villa was to represent the Augustan Age which he and his friends saw as the high water mark of Western civilisation, and he wanted to influence a new Augustan Age.

Visitors to Chiswick House & Gardens can view the obelisk at Burlington Gate and next to the Ionic Temple.

Sources used:

- Obelisk by Curran, Grafton, Long and Weiss (2009)

- Raising Obelisks: Unearthing a Long Forgotten Ancient Egyptian Invention by Best and al Hashash (2020)

- Recording Britain by Saunders (2011)

- The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, His Villa & Garden at Chiswick, by Harris (1994)

- The Obelisks of Egypt : Skyscrapers of the Past, by Habachi (1906)

- The problem of the obelisks, from a study of the unfinished obelisk at Aswan, by Engelbach (1923)